Title: The Crucifixion Icon

Artist Name: Unknown Byzantine Master

Genre: Byzantine Religious Icon

Date: 8th Century CE

Dimensions: Unknown

Materials: Egg tempera and gold leaf on wood panel

Location: Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai, Egypt

The Dark Canvas of Divine Mystery

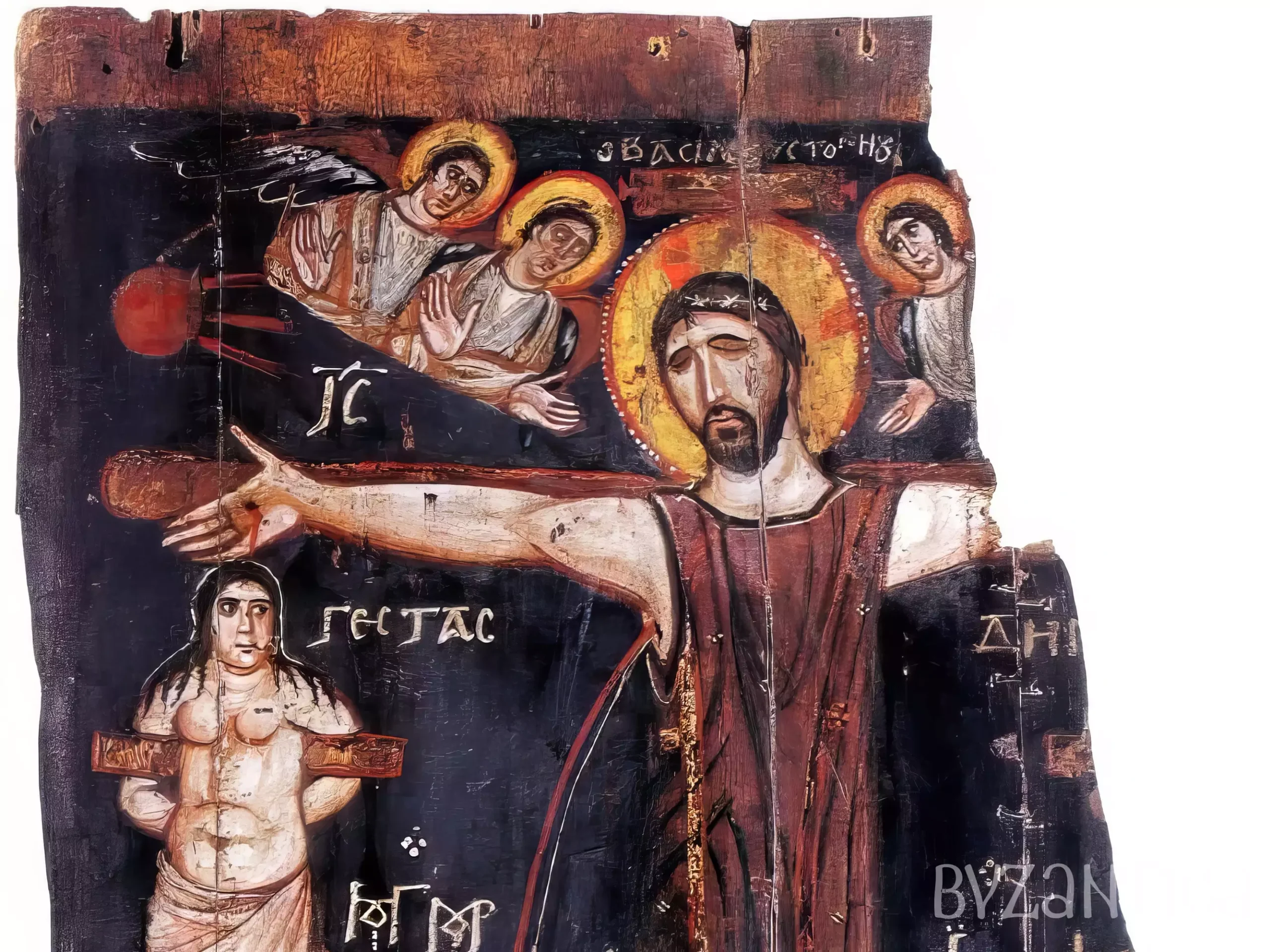

The Sinai Crucifixion emerges through centuries as a profound manifestation of divine artistry, its 8th century CE origins marked within Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai. This sacred work transcends mere artistic convention, speaking in visual dialectics that pierce the depths of contemplative understanding.

As I stand before this icon, the darkness seizes my consciousness – not as absence but as primordial presence. The artist’s choice of an almost black expanse creates not merely contrast but ontological depth, drawing the observer into realms beyond temporal constraints. This void becomes pregnant with meaning, a space where divine and human nature converge in silent dialogue.

The figure of Christ commands my gaze with sovereign authority. His form, rendered in earthy pigments, radiates an inner illumination that defies physical laws. I observe how the reddish-brown of His garment transforms into a vessel of uncreated light. Time’s passage has gifted the work with subtle fissures in its surface, each crack paradoxically strengthening its sacred potency.

The work’s spatial arrangement abandons earthly perspective for divine geometry. Three angelic beings create a celestial hierarchy above Christ, their triangular formation directing consciousness toward the central mystery. Their countenances hold the tension between divine understanding and mortal sorrow. The Theotokos, clothed in her characteristic orange-red vestment, stands as witness to both cosmic triumph and maternal loss.

Each stroke of the master’s brush carries theological weight. The surface texture achieves a remarkable duality – simultaneously asserting its material presence while pointing toward immaterial truth. The restricted chromatic range – predominantly earth tones, deep reds, and selective applications of gold – creates an emotional intensity that transcends mere color theory. Light emanates from within the sacred figures, suggesting divine self-manifestation rather than external illumination.

Christ’s hands particularly arrest my attention. Their extension embodies the paradox of kenosis and victory – theological truth manifested through visual rhetoric. While the proportions diverge from anatomical precision, they achieve a higher order of truth, one that speaks to spiritual rather than physical reality.

In this sacred space, every element participates in a visual theology that transforms mere pigment and wood into a portal of divine encounter. The artist’s mastery lies not in naturalistic representation but in creating a threshold where temporal and eternal intersect in profound silence.

The Sacred Geometry of Color and Form

Looking at the lower section of this remarkable icon, I find myself drawn to subtle details that speak volumes about the artist’s theological understanding. The way figures are arranged creates an almost musical rhythm – there’s a visual cadence that pulls the eye in circular motions, yet always returns to Christ’s central presence. The Sinai Crucifixion expresses something I rarely see in other works of this period: a profound understanding of how sacred geometry can serve spiritual truth.

The way light plays across the surface reminds me of early morning sun catching dust motes in a monastery chapel. There’s a particular quality to the aging that enhances rather than diminishes – each crack and wear mark adds depth, like wrinkles on a sage’s face. The artist’s handling of the Panagia’s garments shows extraordinary sensitivity. The folds don’t just suggest fabric; they create a visual poetry of grief and dignity.

What fascinates me most is how the artist solved the problem of depicting divine presence in material form. The figures at the bottom of the composition don’t just occupy space – they exist in a kind of theological dimension where physical laws yield to spiritual truth. I notice how their poses echo ancient gestures of lamentation, yet transcend mere mimicry to express something deeply personal and immediate.

The paint application reveals layers of meaning through technique. Thin washes of color build up to create subtle modulations in the flesh tones, while more opaque passages provide structural strength. The artist’s understanding of color psychology shows in the way warmer tones draw forward while cooler ones recede, creating a sacred space that seems to breathe with divine presence.

Looking closely at the faces, particularly those of the attendant figures, I see how the artist used shadow not just to model form, but to suggest inner contemplation. The expressions carry a weight of understanding that transcends simple emotion. Each face becomes a window into the mystery being enacted – not mere observers but participants in a divine drama.

The damage at the top edge of the icon, rather than diminishing its power, adds an almost prophetic quality. Like ancient scripture fragments, these traces of time remind us that sacred art lives in dialogue with eternity. The surviving elements gain additional power through what’s been lost, suggesting truths beyond what remains visible.

Divine Expression in Sacred Space

In this arresting fragment of the 8th-century Sinai Crucifixion, which I observe daily at Saint Catherine’s Monastery, the mastery of sacred portraiture reaches heights that still astonish after centuries of contemplation. The sacred triangle formed by Christ’s countenance and the three attending angels creates not merely a compositional device, but a theological statement written in pigment and presence.

The face of Christ beneath my studying gaze reveals itself as a masterwork of spiritual paradox. Each careful layer of earth-derived pigment builds not just physical depth, but metaphysical meaning. The dark eyes, shaped like ancient almonds, hold a profound duality – at once penetrating outward while drawing inward into depths beyond mortal comprehension. The master achieved this through an exquisite understanding of shadow’s sacred potential, crafting eye sockets that both invite and transcend earthly vision.

Christ’s beard emerges as a meditation on divine incarnation. Unlike the abstracted patterns that would later dominate Byzantine iconography, here each individual stroke suggests the tangible reality of the God-man. The profound brown pigment, extracted from the earth He created, has transformed through time’s alchemy into a radiance that both emerges from and transcends the deeper skin tones surrounding it.

The triad of angels above presents itself as a study in celestial psychology. Though unified in their basic forms, each face carries its own weight of divine concern. The central angel’s features bear deeper marks of holy worry, while its companions manifest different degrees of eternal contemplation. Their haloes, worked in gold now transformed by oxidation’s touch, create a sacred rhythm against Christ’s larger nimbus.

In my careful study of the color choices, I notice how the artist achieved profound effects through divine restraint. The palette draws from earth itself – ochres speaking of Jerusalem’s hills, siennas echoing desert sands, umbers deep as sacred shadows. Christ’s reddish-brown garment stands as a vertical axis mundi, while the angels’ lighter vestments suggest heaven’s movement above.

The Greek inscription, though time has taken its toll, remains both text and texture. These letters transcend mere labeling to become integral elements of the icon’s sacred geometry, each character a stepping stone between human language and divine truth.

As my eyes trace the relationship between this detail and the whole, I recognize an intuitive grasp of visual theology that preceded formal articulation by centuries. Christ’s head, tilted with divine intent, guides our earthly vision toward the mourners below, while angelic gestures lift our contemplation heavenward in an endless cycle of sacred viewing.

Sacred Sorrow in Crimson and Gold

This profound detail from the 8th-century Sinai Crucifixion, preserved at Saint Catherine’s Monastery, captures the Theotokos in a moment of transcendent grief. The artist’s handling of this figure showcases an extraordinary understanding of how material technique can express spiritual truth.

The deep crimson of her garment dominates the composition, created through layers of mineral pigments that have aged into something more profound than mere color. The way the folds catch light creates a visual rhythm that somehow manages to express both dignity and distress. Her gesture – the raised hand touching her face – speaks volumes about contained emotion, a grief too deep for obvious display.

What strikes me most is the artist’s treatment of her face. The subtle modeling around the eyes and cheeks suggests tears without actually depicting them – a masterful choice that elevates the emotional impact. The slight tilt of her head, emphasized by the curve of her maphorion, creates a visual connection with Christ above while maintaining her own spiritual presence.

The golden nimbus surrounding her head shows fascinating technical sophistication. The artist applied what appears to be gold leaf in a pattern that creates subtle variations in how light plays across its surface. Time has worn away some areas, creating an almost ethereal effect that enhances rather than diminishes the spiritual power.

The paint application reveals remarkable sensitivity. Looking closely at the face, one can see how the artist built up layers of flesh tones, working from darker to lighter values with extraordinary control. The shadows around the eyes don’t just create form – they suggest depths of contemplation that transcend physical representation.

The figure’s positioning within the larger composition is particularly meaningful. She stands at the base of the cross, yet her presence has its own gravitational pull within the sacred space. The way her garment flows creates subtle diagonal lines that lead the eye upward toward Christ while simultaneously anchoring the lower portion of the composition.

Some of the most affecting details are the smallest – the way her fingers curl in that gesture of grief, how the highlights on her garment create a sense of movement even in stillness, the careful delineation of the fold of cloth near her throat that somehow manages to suggest the tension of contained emotion.

Legacy of Sacred Artistry

This 8th-century Sinai Crucifixion radiates a sacred presence that pierces through time itself. Gazing at its weathered surface, I discern not merely pigments and forms, but a divine language written in visual poetry. The unknown master’s hand moved with extraordinary sensitivity, each gesture carrying profound theological weight.

The spatial composition strikes me as particularly masterful. Against backgrounds of deep, almost infinite darkness, the figures emerge with startling immediacy. The artist’s manipulation of earth pigments creates a visual hierarchy that guides my eye from terrestrial suffering toward celestial mystery. These are not mere aesthetic choices – they constitute a complete visual theology, where every shade and shadow carries metaphysical significance.

When I study the icon’s material presence, I notice how the paint sits in whisper-thin layers, each one contributing to an overall luminosity that seems to emerge from within rather than reflect from without. This technical achievement perfectly mirrors the Byzantine understanding of matter’s capacity to manifest divine truth. The surface bears witness to centuries of devotional gazing – tiny cracks and wear patterns that speak of countless encounters between human and divine.

The emotional core of the work lies in its treatment of the sacred figures. The Theotokos and Christ exist in a shared space of suffering and transcendence, their relationship expressed through subtle visual harmonies. I observe how the tilt of Mary’s head answers the angle of Christ’s body, how their hands echo each other in gestures of both acceptance and offering. These are not separate moments but a single reality made visible through artistic mastery.

The current condition of the icon, marked by time’s passing, only intensifies its spiritual power. Each trace of age reads as a record of prayer, each patch of wear as evidence of centuries of faithful attention. The surface has become a palimpsest of devotion, where physical aging paradoxically reveals timeless truth.

This masterwork exemplifies the highest achievement of sacred art – the complete fusion of artistic means and spiritual ends. I see how every formal decision serves both aesthetic and theological purposes simultaneously. The artist knew that true sacred art must function on multiple levels at once, engaging physical sight while awakening inner vision. This profound synthesis makes the Sinai Crucifixion not simply an historical treasure but a living testament to art’s capacity to manifest divine presence in material form.

The Unknown Master of Mount Sinai

The artist who created the 8th-century Sinai Crucifixion remains anonymous, yet their masterful technique speaks volumes about their training and spiritual depth. Working within the sacred confines of Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai, this unknown master demonstrated exceptional understanding of both artistic technique and theological symbolism.

The artist’s style suggests training in one of the major Byzantine artistic centers, possibly Constantinople itself. Their sophisticated handling of color and form shows familiarity with classical traditions while moving beyond them toward a more spiritualized mode of representation. What sets this master apart is their extraordinary ability to unite technical precision with spiritual insight.

Looking at the quality of line work and paint application, there’s evidence of a highly developed workshop tradition. Yet this artist brought something uniquely personal to their work – a profound understanding of how material technique can serve spiritual truth. Their handling of facial expressions, particularly in the figure of Christ, reveals someone who thought deeply about the relationship between divine and human nature.

Patra, 2002

© Byzantica.com. Permission is granted to use this material for non-commercial purposes only, provided that you include proper attribution to ‘Byzantica.com UHD Christian Gallery (www.byzantica.com)’ and an active hyperlink to this post.