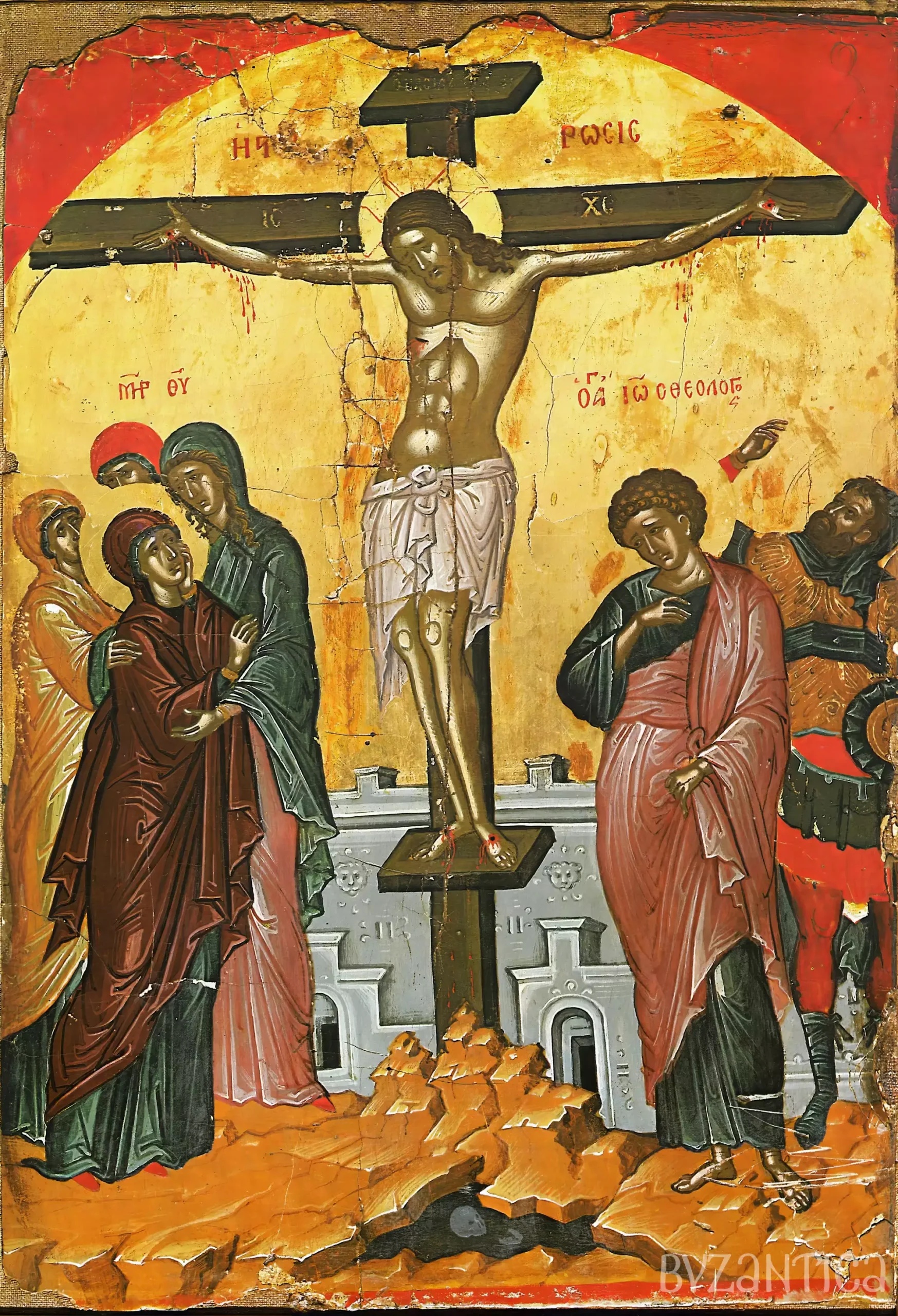

Crucifixion icon by Theophanes

Title: The Crucifixion

Artist Name: Theophanes the Cretan (Theophanes Strelitzas)

Genre: Religious Orthodox Icon

Date: 16th century AD

Materials: Egg tempera and gold leaf on wood panel

Location: Stavronikita Monastery, Mount Athos, Greece

The Sacred Moment

Standing before this icon, I’m struck by its raw emotional power. The gold background burns with inner light, not just decoration but a window into divine reality. Against it, Christ’s body hangs with a strange weightlessness, both physical and transcendent.

As K Vapheiades notes in his study of Cretan artistic activity in Western Thessaly, Theophanes brought unprecedented psychological depth to his figures. I see this in how he’s handled the mourners – they’re not just witnesses but participants in this cosmic drama. The Virgin Mary’s face carries such profound sorrow, yet there’s dignity in how she holds herself. John the Beloved’s red robe catches the light like fresh blood.

The technique here is masterful. Each brushstroke feels deliberate yet fluid. The modeling of Christ’s body shows deep anatomical understanding, but it’s transformed into something beyond mere physical representation. Dark shadows pool in the folds of cloth, creating rhythms that pull the eye upward toward the cross.

What gets me is how the space works – it’s both flat and deep at once. The buildings of Jerusalem sit like stage props behind the main scene, while the rocky ground splits and buckles beneath the cross. This isn’t just artistic convention – it’s showing how this moment shatters ordinary reality. The skull at the base of the cross (Adam’s skull, according to tradition) peers out from its cave, linking Christ’s death to humanity’s first fall.

The paint surface itself tells a story – slight crackling in the gold leaf, tiny losses that speak of centuries of devotion. Yet the power of the image cuts through time. The inscription above Christ, though partially worn, still proclaims its message in formal Greek letters. The balance of red and gold creates a visual heartbeat that seems to pulse through the whole composition.

This is more than art – it’s theology in color and form. But it’s theology that hits you in the gut first, makes you feel before you think. The way the cross dominates the space, how Christ’s body curves in its final breath – these speak directly to human experience of loss and transcendence.

The Crucifixion icon by Theophanes: Technique and Symbolism

Looking deeper at this masterwork, I notice how R Gothoni helps us understand the monastic context that shaped icons like this one. Athonite monasticism created a unique environment where art and spirituality merged completely. That deep connection shows in every aspect of this icon.

What strikes me now is the artist’s use of perspective. The buildings don’t follow natural rules – they tilt and lean, creating a psychological space rather than a physical one. This isn’t a mistake or limitation. It’s a deliberate choice that makes the spiritual world feel immediate and real.

The figures around the cross form an emotional choreography. On the left, Mary’s companions support her in her grief. Their poses echo each other, creating a visual rhythm that pulls us into their shared sorrow. On the right, John’s red robe stands out against the muted tones of the other figures, marking him as the beloved disciple.

C Terezis explores how Byzantine icons bridge beauty and the sublime. I see that tension here in how Theophanes handles Christ’s body. There’s a terrible beauty in how he depicts the moment of death – the slight curve of the torso, the downturned head. It’s painful to look at, yet impossible to look away from.

The technical mastery is clear in small details – the way cloth folds catch light, how shadows deepen gradually rather than suddenly. The artist knows exactly how to guide our eye through the composition. A subtle line of rocks leads up to the cross, then Christ’s arms spread wide, embracing the whole scene.

The gold background isn’t flat or static. It seems to shift and pulse as you move, creating an almost living presence. This effect comes from how the gold leaf was applied – countless tiny pieces carefully burnished to catch light differently. When candles would have lit this icon, these variations would have created a subtle shimmer, as if the divine light itself was moving through the scene.

Every element serves both artistic and spiritual purposes. The skull at the base of the cross isn’t just a memento mori – it’s Adam’s skull, according to tradition, linking Christ’s sacrifice to humanity’s first fall. The rocks split and break, showing how this moment fractures the very foundations of the world.

Legacy of the Crucifixion icon by Theophanes

The final minutes of daylight stream through the monastery windows, casting a special glow on this icon. In these quiet moments, the paint surface takes on new life. Age marks and slight wear become meaningful – they’re traces of countless prayers, of hands reaching out to touch divinity through art.

The architectural elements carry more weight now. Those simple buildings in the background aren’t just stage settings – they represent Jerusalem, yes, but also every city, every human community faced with divine presence. The walls seem both solid and transparent, as if struggling to contain the cosmic drama unfolding before them.

I find myself drawn to the subtle interplay between human imperfection and divine perfection in this work. The figures of Mary and John show such raw emotion, yet they’re contained within strict compositional bounds. Their grief doesn’t spill over into chaos – it’s transformed into something universal, speaking across centuries.

The balance of elements feels both calculated and natural. Dark passages of paint create valleys and peaks across the surface, leading always back to Christ’s figure. The cross itself becomes an axis mundi, a fixed point around which the entire composition turns. Even the smallest details – a fold of cloth, a glint of gold – play their part in this visual symphony.

What moves me most is how this icon somehow bridges time. When I stand before it, I’m connected to generations of viewers who’ve stood in this same spot, seeking comfort or understanding. The artist’s hand, though centuries distant, feels present in every brushstroke. The icon isn’t just showing us something – it’s teaching us how to see.

The longer I look, the more this feels like a living dialogue between artist, viewer, and divine mystery. There’s something profound in how Theophanes managed to make suffering beautiful without diminishing its reality. The icon doesn’t dodge the horror of crucifixion, but it transforms it into something that opens up rather than closes down human understanding.

The Anatomy of Divine Sacrifice

This detail from the Crucifixion icon by Theophanes pulls us closer to the heart of the composition. Here, Christ’s torso becomes a study in sacred anatomy – not just physical but symbolic. Against the radiant gold background, the modeling of the body shows extraordinary subtlety. Light seems to play across the surface, creating gentle transitions from illuminated flesh to shadow.

The artist’s technique reveals deep understanding of both human form and divine representation. The ribs are suggested rather than anatomically detailed, creating a rhythm of light and shadow that draws the eye upward. The slightly curved posture speaks of both suffering and transcendence – this is a body in pain, yet one that maintains impossible grace.

Each brushstroke feels deliberate yet fluid. The highlights are built up in thin layers, creating a luminous quality that seems to emerge from within rather than just reflecting external light. Dark shadows pool at key points – under the arms, along the side – but they never become harsh or dramatic. Instead, they create a gentle progression that guides our eye through the sacred narrative.

The treatment of the flesh tones is remarkable. Rather than the stark pallor often seen in crucifixion scenes, here there’s warmth and life in the skin tones. Small touches of red in the wounds don’t overwhelm but remind us of Christ’s humanity. The cloth draped at the waist shows masterful handling of white – it’s not just white, but contains subtle variations that make it feel dimensional and real.

What strikes me most is how this detail balances between abstraction and reality. The body is clearly recognizable, yet there’s something otherworldly in how it’s rendered. The proportions are slightly elongated, the muscles suggested rather than anatomically precise. This isn’t meant to be a medical illustration – it’s a window into divine mystery.

The old damage visible in places – small cracks and wear – adds another layer of meaning. These marks of time remind us how long this image has served as a focus of devotion. They’re not flaws but evidence of the icon’s living presence in countless prayers and contemplations.

Timeless Echoes in Sacred Art

Looking back at the Crucifixion icon by Theophanes, I’m drawn to its enduring power across centuries. Hidden in a corner of Mount Athos, this artwork speaks to both past and present. The mix of extraordinary skill and deep spiritual understanding creates something that transcends its time.

The physical details still catch my eye – that stunning interplay between gold leaf and earth tones, the way Christ’s form commands the space without dominating it. But what lingers most is how this icon makes sacred time feel present. It doesn’t just show a historical moment – it opens a window into something eternal.

The way Theophanes handled paint itself tells a story. Those careful layers building up flesh tones, the confident strokes defining drapery – they show an artist completely in command of his medium, yet humble before his subject. You can almost feel the weight of tradition in each brushstroke, balanced perfectly with personal insight and skill.

What moves me most is how this icon still works exactly as intended. After all these centuries, it still draws viewers into contemplation, still guides the eye and heart through its sacred narrative. The craftsmanship serves the spiritual purpose so perfectly that the two become inseparable.

As the light shifts and shadows move across its surface, this icon reminds me that great religious art isn’t frozen in time – it lives and breathes with each new viewer. The Crucifixion icon by Theophanes stands as testament to how human hands can create something that touches the divine.

Theophanes the Cretan: Master of Sacred Art

Theophanes the Cretan, also known as Theophanes Strelitzas-Bathas, was a 16th-century icon painter who profoundly influenced post-Byzantine art. Working primarily on Mount Athos, he created some of the most remarkable examples of Orthodox iconography. The Crucifixion icon showcases his mature style, combining traditional Byzantine techniques with a distinct personal touch that set him apart from his contemporaries.

His work at the Stavronikita Monastery represents the peak of his artistic achievement. What strikes me about his technique is the exceptional balance between adherence to canonical forms and artistic innovation. In this Crucifixion icon, I see his masterful handling of color transitions and his unique approach to creating spiritual depth through subtle modeling of forms.

As a master of the Cretan school of painting, Theophanes brought together the strict requirements of Orthodox iconography with elements of humanist painting that were emerging in his time. The result is work that feels both timeless and immediate, speaking across centuries while remaining deeply rooted in Orthodox tradition.

© Byzantica.com. For non-commercial use with attribution and link to byzantica.com

The analysis presented here reflects a personal interpretation of the artwork. While based on research and scholarly sources, art interpretation is subjective, and different viewers may have varied perspectives. These insights are meant to encourage reflection, not as definitive conclusions. The image has been digitally enhanced, and the article’s content is entirely original, © Byzantica.com. Additionally, this post features a high-resolution version of the artwork, with dimensions exceeding 2000 pixels, allowing for a closer examination of its details.

Bibliography

- Gothoni, R. “Pilgrimage and the becoming of Athonite monasticism.” In Nineteenth-Century European Pilgrimages. London: Taylor & Francis, 2020.

- Terezis, C. “The Byzantine icon as an expression of the composition of the ‘Beautiful’ with the ‘Sublime’.” Dianoesis (2022): 37788.

- Vapheiades, K. The Artistic Activity of Theophanes the Cretan in Western Thessaly and the Emergence of the ‘Cretan School’ of Painting.” Analecta Stagorum et Meteororum (2022): 38863.