Christ Pantocrator imagery

Title: Christ Pantocrator Icon

Artist Name: Unknown Master of Constantinople School

Genre: Byzantine Religious Icon

Date: 13th century AD

Materials: Egg tempera and gold leaf on wood panel

Location: Vatopedi Monastery, Mount Athos, Greece

The Sacred Presence: A Window to Divinity

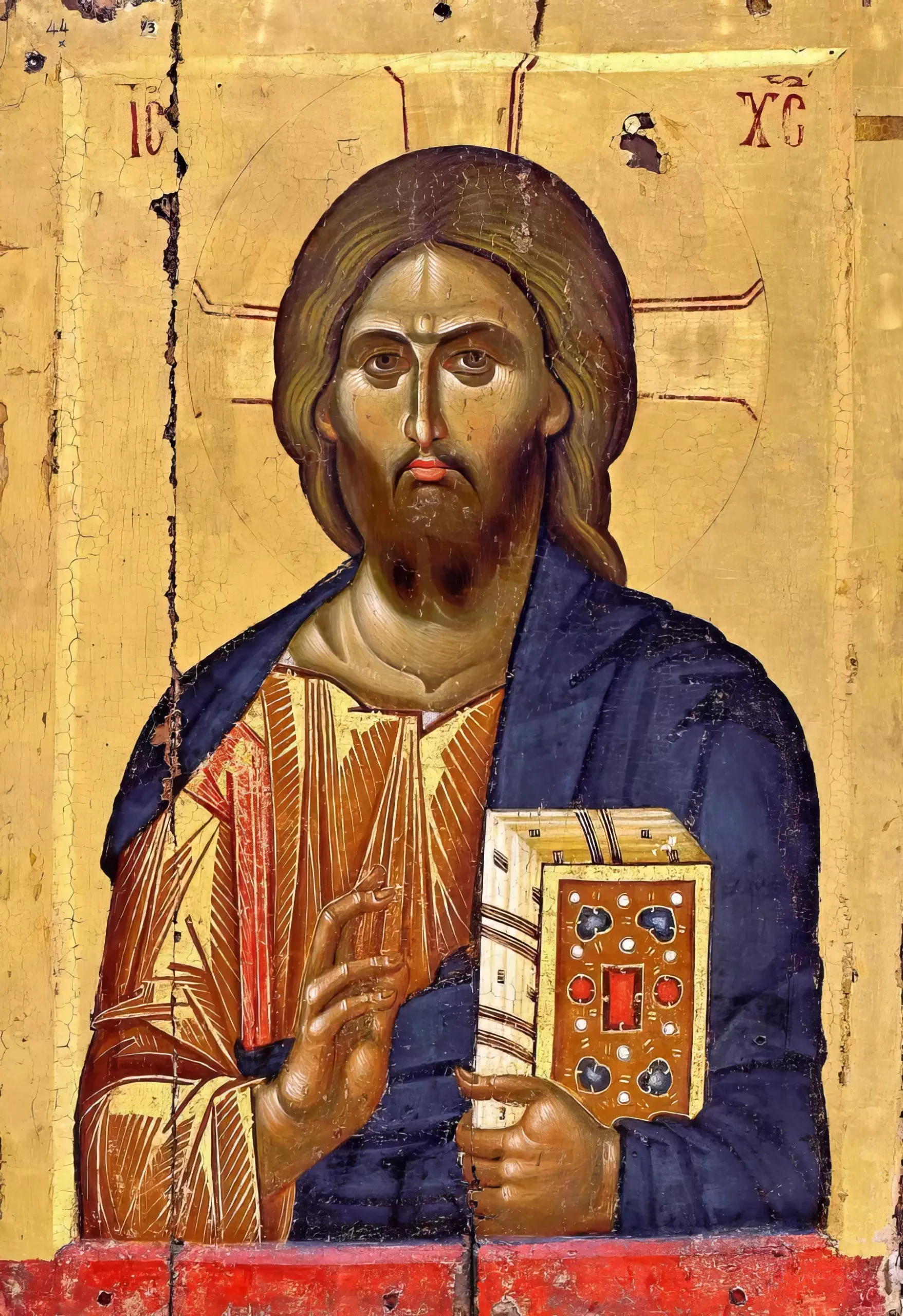

The gold leaf catches the light, creating an otherworldly radiance that pulls me in. This Christ Pantocrator from Vatopedi Monastery stands as one of the most striking examples of 13th-century Byzantine art. The icon’s raw power lies in its directness – Christ’s penetrating gaze meets mine with an intensity that’s hard to look away from.

The artist has achieved something remarkable here. The face of Christ emerges from the gold background with an almost three-dimensional quality. Those deep-set eyes, framed by strong brows and highlighted with touches of white, seem to follow you around the room. It’s a technique that creates an unsettling intimacy – you can’t escape that searching gaze.

This icon shows the traditional Pantocrator pose – Christ holding a jeweled Gospel book in his left hand while his right hand makes the gesture of blessing. The blue cloak (himation) draped over a golden-orange undergarment (chiton) uses color symbolically. As A Johnson notes in his research on Byzantine iconography, “The interplay of divine gold and earthly blue represents Christ’s dual nature as both God and man.” You can see how the colors interact – the warm glow of divinity showing through the cool tones of humanity.

The craftsmanship fascinates me. Looking closely, you can see how the artist built up the face with careful layering of paint. The shadows around the nose and cheeks use a dark green underpainting technique characteristic of Constantinople workshops. The highlights are done with pure white in quick, confident strokes – evidence of a master’s hand at work.

What draws me in most is the profound humanity in this divine face. Yes, this is the Ruler of All (Pantocrator), but the artist has captured something deeply personal too. There’s both stern judgment and infinite compassion in that expression. The slightly asymmetrical features and the gentle curve of the mouth make Christ seem present and real, not just a remote symbol.

I’ll examine the deeper theological and cultural significance of this masterpiece in the next chapter, but first I wanted to share my direct impressions of encountering this remarkable work of sacred art. It’s the kind of image that stays with you long after you’ve turned away.

Divine Power and Human Connection: The Icon’s Sacred Language

Standing before this masterwork, I’m struck by how the artist balanced divine majesty with human connection. The composition draws from time-honored Byzantine traditions, yet adds subtle innovations that bring fresh life to the conventional Pantocrator formula. As P Sofragiu discusses in his analysis of Vatopedi’s artwork, “The icons serve not merely as art objects but as windows into the divine realm, creating a direct connection between the viewer and the sacred.”

The way light plays across the surface creates an almost living quality. Shadows deepen around Christ’s eyes, giving them remarkable depth. The artist used a technique where darker tones were laid down first, then gradually built up with lighter colors. This creates an inner luminosity that seems to shine from within the panel itself.

What fascinates me is how the unknown master handled Christ’s expression. There’s authority there, yes, but also understanding. The slight tilt of the head suggests attentiveness to human prayers. The eyes hold wisdom but not judgment. As KM Vapheiades notes in his study of Mount Athos painting styles, this more approachable interpretation of the Pantocrator emerged during a period when Byzantine art was becoming more emotionally expressive.

Looking at the Gospel book Christ holds, I notice how carefully the jewels are rendered. Each one catches light differently – some flash bright, others glow softly. The artist didn’t just paint decorations; they created a sense of precious materials that symbolize the priceless nature of divine wisdom. The red and blue of the book’s cover echo the colors in Christ’s robes, binding the composition together.

The background’s gold leaf does more than create splendor – it removes the figure from earthly space and time. Yet the solid presence of Christ’s form, especially in the strong modeling of the face and hands, keeps him connected to human experience. This perfect balance between transcendence and immanence is what gives the icon its spiritual power.

The craftsmanship shows remarkable control over the medium. Fine lines define features with precision, while broader strokes in the clothing create rhythm and movement. Even the tiniest details, like the individual hairs in Christ’s beard, are executed with extraordinary care. This attention to detail wasn’t just artistic showing off – it was an act of devotion.

The Art of Sacred Space: Iconographic Heritage and Meaning

This icon exemplifies how Byzantine artists mastered the creation of sacred space through visual language. The stark frontality of Christ’s pose creates an immediate confrontation between viewer and divine presence. Yet there’s an underlying gentleness in the execution that draws you in rather than pushing you away.

The composition follows strict theological and artistic rules that developed over centuries. The proportions aren’t naturalistic – they’re intentionally hieratic, with the head slightly larger in relation to the body. This subtle distortion emphasizes Christ’s spiritual rather than physical nature. The facial features are idealized yet retain enough individual character to feel present and real.

What moves me most is how the artist handled transitions between light and shadow. The modeling is extraordinarily subtle, especially around the eyes and mouth. Darkness deepens gradually into the eye sockets, then brightens with precise highlights that create that famous penetrating gaze. The effect is both ethereal and deeply human.

The border design merits close attention too. Simple red bands frame the image, focusing attention inward while setting boundaries between sacred and mundane space. Small losses in the gilding along the edges reveal the red preparation layer beneath – a glimpse into the icon’s material history that somehow makes it feel more authentic.

The inscription follows traditional Byzantine conventions but shows distinctive calligraphic flourishes typical of 13th-century metropolitan workshops. The letters have an architectural quality, their strong verticals and curves echoing the structured harmony of the main image.

What we’re seeing is more than just masterful technique – it’s the culmination of centuries of theological and artistic development. This icon creates a contemplative space that transcends its physical boundaries. Through careful observation, we begin to understand how Byzantine artists achieved this transformative power through their sophisticated command of both material and spiritual elements.

The care taken with every detail reflects the profound purpose these works served in Orthodox worship. From the precise layering of paint to create luminous flesh tones, to the measured application of highlights that suggest divine light, nothing here is arbitrary. Each artistic choice serves the icon’s ultimate goal – to make the divine present and accessible while maintaining its essential mystery.

The Sacred Gaze: Analyzing the Face of Christ

The face of Christ emerges from the gold ground with arresting immediacy. Here in this detailed view, the artist’s consummate skill in creating divine presence becomes even more apparent. The treatment of the flesh tones shows extraordinary sophistication – warm ochres build up gradually to create a sense of living form, while subtle green undertones in the shadows add depth and mystery to the modeling.

Every element serves both artistic and theological purposes. The strong central parting of the hair frames the face symmetrically, yet slight asymmetries in the features bring a profound humanity to the divine countenance. The eyes particularly reward close study – the pupils are placed slightly asymmetrically, creating that famous effect where Christ seems to look both at and through the viewer simultaneously.

The artist’s technique reveals deep understanding of how to create sacred presence through paint. Fine hatching builds up the beard with remarkable delicacy, each stroke precisely placed. The highlights on the nose, cheeks and forehead are applied with controlled confidence – bright but never harsh. Most striking is how the artist handled the eyes, using deeper browns in the sockets that make the whites seem to gleam from within.

The condition of the icon lets us see something of its history. Fine cracks in the surface reveal the icon’s age, yet also its durability. The gold ground shows subtle wear patterns that suggest centuries of devotional use. These marks of time paradoxically make the face feel more present and alive – this is an image that has witnessed countless prayers and maintained its power to move hearts.

The expression achieves that characteristically Byzantine balance between majesty and mercy. The slightly furrowed brow suggests both authority and concern, while the small, firmly set mouth conveys determination without severity. Every feature serves this dual purpose – conveying both Christ’s divine authority and his loving engagement with humanity.

Eternal Presence

Time seems to pause before this remarkable icon. After careful study, I’m struck by how the unknown master of Vatopedi managed to create something that transcends its historical moment. This Christ Pantocrator isn’t just a masterpiece of Byzantine art – it’s a living testament to how sacred art can bridge centuries and speak to the deepest human longings.

The artist’s technical brilliance served a higher purpose. Each careful brushstroke, each subtle transition of color, each interplay of light and shadow was executed with both supreme skill and profound spiritual understanding. The result is an image that continues to fulfill its intended function – creating a space for genuine encounter between the human and divine.

What moves me most is how this icon balances opposing qualities. It’s both deeply traditional and uniquely personal, both hieratic and intimate, both timeless and immediate. The artist worked within strict canonical requirements yet found space for creative expression that makes this particular image uniquely powerful.

The face we see here has gazed out at countless worshippers over centuries. While the gold ground has dimmed and fine cracks mark the surface, these signs of age only add to its authenticity. They remind us that this is not just a masterwork of religious art, but a living piece of Christian tradition that has accompanied generations of believers in their spiritual journey.

Looking at it one final time, I’m reminded that great religious art doesn’t just represent – it presents. This icon doesn’t merely show us an image of Christ; it makes his presence felt in a way that mere words struggle to capture. That’s the enduring miracle of Byzantine sacred art at its finest.

The Anonymous Master: Byzantine Icon Painting in the 13th Century

The artist of this magnificent Christ Pantocrator remains unknown, as was common for Byzantine icon painters who saw their work as an act of devotion rather than personal expression. Yet the technical mastery and spiritual depth displayed here point to one of the leading artists working in Constantinople’s most prestigious workshops during the 13th century.

Looking at this icon, I see the culmination of centuries of Byzantine artistic tradition filtered through exceptional individual talent. The sophistication of the modeling, the psychological depth of the expression, and the perfect balance of divine majesty with human accessibility mark this as the work of a master at the height of their powers.

The artist worked within the strict canonical requirements of Orthodox icon painting while finding subtle ways to infuse the image with unique power and presence. Their command of the demanding egg tempera technique, skilled use of chrysography (gold highlighting) in the garments, and masterful creation of luminous flesh tones through multiple thin layers of paint reveal years of rigorous training in Constantinople’s finest studios.

© Byzantica.com. For non-commercial use with attribution and link to byzantica.com

The analysis presented here reflects a personal interpretation of the artwork. While based on research and scholarly sources, art interpretation is subjective, and different viewers may have varied perspectives. These insights are meant to encourage reflection, not as definitive conclusions.

Bibliography

- Johnson, A. “Christ Pantocrator: God, Emperor, and Philosopher in Byzantine Iconography.” PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2023.

- Sofragiu, P. “The Mural Paintings from the Exonarthex of Vatopedi Monastery’s Katholikon.” European Journal of Science and Theology 8, no. 2 (2012): 51-66.

- Vapheiades, KM. A Reassessment of Middle Byzantine Monumental Painting on Mount Athos.” Zograf 45 (2021): 79-101.