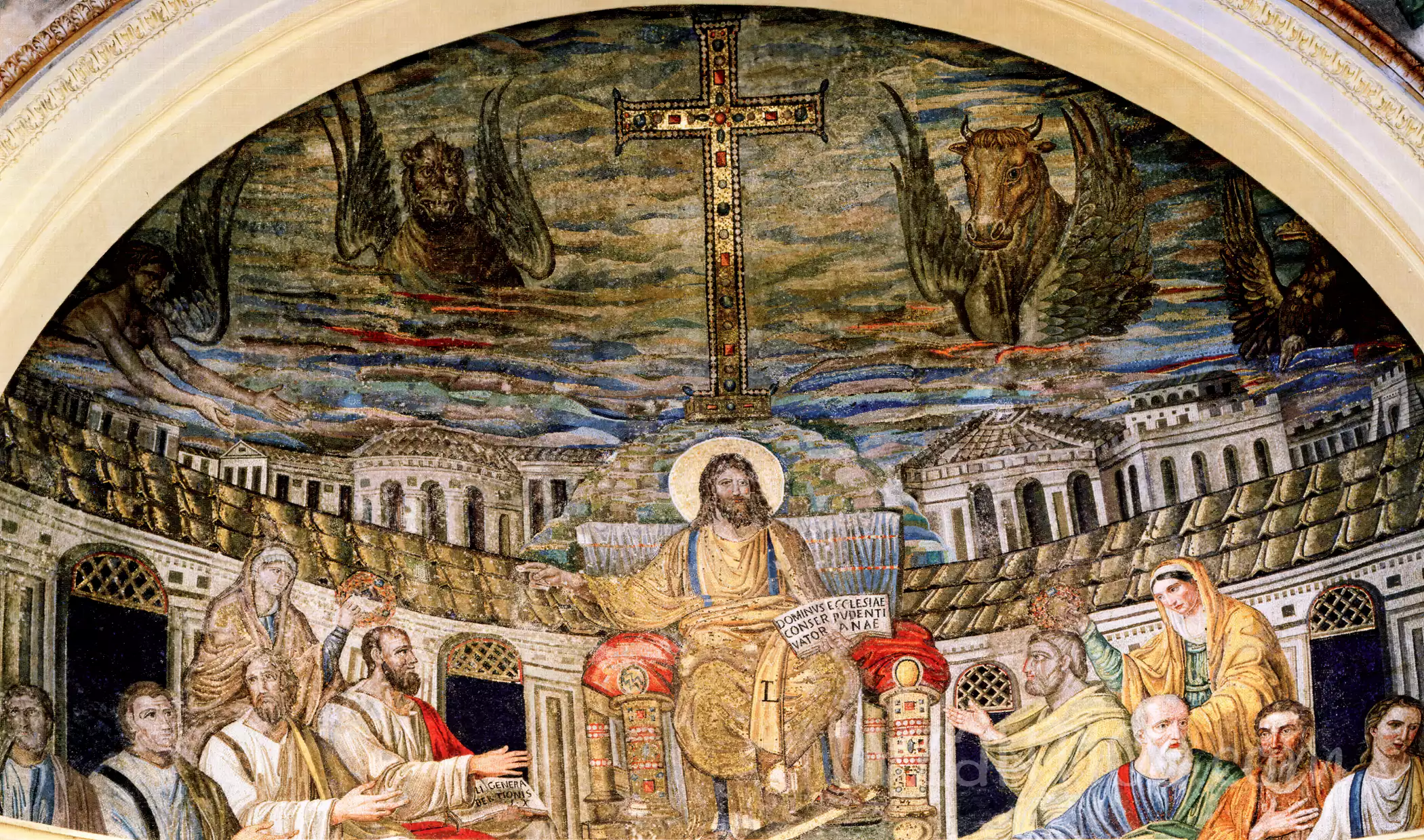

Christ in Majesty mosaic

Title: Christ in Majesty with Apostles

Artist Name: Unknown Roman mosaic artisans

Genre: Early Christian apsidal mosaic

Date: Early 5th century AD

Materials: Glass and stone tesserae, gold leaf

Location: Santa Pudenziana, Rome

Origins and Historical Context

Within the ancient walls of Santa Pudenziana, Rome’s oldest surviving church, a remarkable mosaic unfolds across the curved space of the apse. The morning light filters through centuries-old windows, illuminating what stands as one of Christianity’s earliest and most significant mosaic programs. This masterwork marks a pivotal moment in early Christian art, as it transitions from Roman imperial imagery to Christian iconography.

The composition centers on a majestic Christ, seated upon a jeweled throne. His golden nimbus catches the light, creating an otherworldly glow that sets apart divine from mortal realms. The artist has rendered Christ not as the Good Shepherd of catacomb paintings, but as a regal figure dressed in imperial gold and purple. As Katherine Dunbabin discusses in her comprehensive study of Roman mosaics, “decorated mosaics to survive in Greece date from the late fifth century”, yet this particular work predates those examples, showing remarkable sophistication in its execution.

The surrounding architecture frames Christ with classical grandeur – a series of colonnaded buildings that Sean Leatherbury suggests represents the heavenly Jerusalem. Above, a jeweled cross stands triumphant against a dramatic sky where the four living creatures – the lion, ox, eagle and man – emerge from stylized clouds, symbolizing the evangelists who would spread Christ’s message throughout the world.

What strikes me most is how the unknown artists managed to blend Roman artistic traditions with emerging Christian symbolism. The apostles, arranged in a senatorial manner, wear togas and maintain the dignity of Roman nobles while representing the new spiritual authority. Their faces show individualized features – a remarkable achievement in mosaic work that speaks to the highest levels of craftsmanship available in early 5th century Rome.

The Christ in Majesty mosaic: A Visual Symphony of Power

Looking up at the curved vault of Santa Pudenziana’s apse, the Christ in Majesty mosaic draws me into its sacred narrative with remarkable force. The artistry merges earthly and heavenly realms through an intricate play of color and form. As B Hamarneh notes in their analysis of early Christian mosaics, such representations were carefully crafted to avoid damage while preserving their holy character.

The palette shifts subtly from golden yellows to deep blues, creating an atmosphere of divine transcendence. Christ’s figure dominates the composition not just through size but through the radiant energy that seems to emanate from his form. The mosaic artists achieved this effect through masterful placement of tesserae – each tiny piece catching and reflecting light differently as one moves through the space below.

A fascinating aspect emerges in the architectural setting behind the figures. Amy Kateusz highlights similar architectural representations in fifth-century Roman churches, though none quite match the sophistication seen here. The buildings appear both solid and ethereal, their colonnades and pediments suggesting both the earthly Rome and its heavenly counterpart.

The apostles’ arrangement speaks volumes about early Christian hierarchy and authority. They sit not as equals but in careful gradation, their poses and gestures creating visual rhythms that lead the eye back to Christ. Their garments flow in gentle curves, the folds picked out in subtly modulated tones that demonstrate remarkable technical skill in mosaic work.

What makes this work particularly striking is its fusion of Roman artistic traditions with emerging Christian symbolism. The architectural backdrop draws from classical conventions while the apocalyptic imagery above – the cross and evangelist symbols – points toward developing Christian iconography. This visual tension perfectly captures a moment of profound cultural transformation in early fifth-century Rome.

Technical Mastery and Theological Symbolism

The technical brilliance of this mosaic reveals itself in countless subtle ways. The gold tesserae catch morning light differently from evening light, creating an ever-changing display that mirrors the divine mysteries they represent. Each piece was set at slightly different angles – a technique that makes the surface come alive as viewers move through the space.

What strikes me most is the sophisticated handling of perspective in the architectural elements. The buildings recede convincingly into space while simultaneously appearing to project forward, creating a dynamic tension between physical and spiritual realms. This spatial ambiguity serves the theological message – we are looking simultaneously at earthly Jerusalem and its heavenly counterpart.

The restoration work, while extensive, has preserved the essential character of the original composition. The faces of Christ and the apostles retain their individualized features, though some areas show clear signs of later intervention. These touch-ups actually add to the work’s historical value, documenting centuries of care and reverence.

Most fascinating is how this mosaic established artistic conventions that would influence Christian art for centuries. The frontal, hieratic pose of Christ, the arrangement of apostles, the apocalyptic symbols – all these elements would become standard features of church decoration. Yet here they appear in one of their earliest and most accomplished forms.

The use of color deserves special attention. Deep blues dominate the upper register, suggesting the vault of heaven, while earthier tones ground the lower sections. Gold tesserae create points of divine light throughout, but they’re used with remarkable restraint. This isn’t the gold-saturated style of later Byzantine work – it’s a more nuanced approach that enhances rather than overwhelms the composition.

The Theological and Cultural Dimensions of Early Christian Art

The Christ in Majesty mosaic in Santa Pudenziana represents a watershed moment in Christian visual theology. The artwork embodies the complex transition from Roman imperial imagery to Christian sacred art, while simultaneously establishing visual conventions that would define religious art for centuries to come.

The theological significance lies primarily in how Christ is presented. Unlike earlier catacomb paintings that showed Christ as the Good Shepherd or teacher, here he appears as the divine ruler of the cosmos. His position echoes Roman imperial iconography, but transforms it into something new – divine authority replacing temporal power. The golden throne, richly decorated in jewels, draws from both Roman and Persian royal imagery, creating a visual language that bridges cultural divides.

The architectural context provides more profound levels of significance. The buildings behind the people reflect the celestial Jerusalem detailed in Revelation, not only decoration. In the setting of early 5th century Rome, when the city’s Christian identity was still developing against the backdrop of its pagan past, this dual portrayal of earthly and celestial realms was especially significant.

Emerging from a strikingly portrayed sky, the four living beings – eagle, lion, ox, and man – link this earthly vision to spiritual revelation. With great theological weight, these icons of the evangelists illustrate how the gospels themselves act as windows between heaven and earth. Renowned as a victorious emblem of Christ’s triumph over death, the central jewelled cross is the Crux Gemmata.

Examining the apostles’ configuration, we find a deliberate hierarchy reflecting early church architecture. Reflecting Rome’s particular importance in early Christianity, Peter and Paul hold prominent roles. Their motions and positions produce visual rhythms that guide our gaze back to Christ, so capturing the theological idea that all power emanates from divine sovereignty.

The historical background of the artwork gives still another level of significance. Designed during a period when Christianity was established itself as the major religion of the Roman Empire, the mosaic offers a bold depiction of heavenly authority linked to Roman cultural norms. While changing old traditions to suit new spiritual purposes, the classical structures and senatorial stances of the apostles speak to educated Roman spectators in their own visual language.

The longevity of the mosaic over centuries of restoration and transformation reflects the church’s own flexibility and tenacity. Though it changes certain original aspects, every intervention has helped us to better grasp how various generations saw and preserved this amazing mix of Christian theology and classical craftsmanship. The works are evidence of a turning point when Christianity started to create its own unique visual language from the rich creative legacy it received.

Legacy of the Christ in Majesty mosaic

A monument to a turning point in Christian art history, the Christ in Majesty mosaic found at Santa Pudenziana It speaks remarkably clearly about the evolution of Roman visual culture into something distinctly Christian over millennia of repair and adaptation.

Art changes. This basic reality resounds in the continuing impact of the mosaic. Underneath this amazing creation now, one could wonder: how early Christians first encountered this extreme synthesis of imperial majesty and heavenly revelation? Perhaps the explanation is in the mosaic’s deft use of space and symbol, which creates a setting in which earthy and celestial spheres seem to collide. The composition invites spectators into a reflective environment in which conventional Roman artistic standards fulfil fresh spiritual purposes.

The Christ in Majesty mosaic shaped the development of Christian art in profound ways. Its sophisticated integration of classical forms with Christian theology created a visual language that would influence religious art for centuries. The careful balance of human and divine elements, the thoughtful use of architectural space, and the masterful handling of color and light all point to artists working at the height of their powers, even as they pioneered new forms of religious expression.

Today, this extraordinary work continues to capture imagination and inspire reflection. It reminds us that great art can bridge cultural divides and speak across centuries, carrying eternal truths in the universal language of visual beauty.

The Unknown Artists of Santa Pudenziana

The Christ in Majesty mosaic was created by unknown artisans working in early 5th century Rome. While the names of these master craftsmen are lost to history, their exceptional skill lives on in every carefully placed tessera. The work shows a sophisticated understanding of classical Roman artistic traditions combined with emerging Christian iconography.

The way the artists use colour, perspective, and symbolic components reveals their ability. Their technical mastery is evident in the subtle colour gradations employed to replicate draperies and faces as well as in the intricate architectural background framing the image. Among the first and most skilled examples of Christian apsidal ornamentation, these unknown masters produced

Working in glass and stone tesserae with gold leaf details, they devised creative methods to produce shadow and light effects. Individual pieces placed at different angles produce a shimmering surface that shifts with the viewer’s position and time of day. This intentional manipulation of light lends a transcending dimension that increases the spiritual impact of the mosaic.

© Byzantica.com. For non-commercial use with attribution and link to byzantica.com

The analysis presented here reflects a personal interpretation of the artwork. While based on research and scholarly sources, art interpretation is subjective, and different viewers may have varied perspectives. These insights are meant to encourage reflection, not as definitive conclusions. The image has been digitally enhanced. The article’s content is entirely original, © Byzantica.com. Additionally, this post features a high-resolution version of the artwork, with dimensions exceeding 2000 pixels, allowing for a closer examination of its details.

Bibliography

- Hamarneh, B. “The Mosaic.” In Petra the Mountain of Aaron: the Finnish Archaeological Project in Jordan, 2008.

- Kateusz, A. “Patterns of Women’s Leadership in Early Christianity.” 2021.

- Dunbabin, KMD. Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World. 1999.

- Leatherbury, SV. “Christian Wall Mosaics and the Creation of Sacred Space.” In The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art, 2018.